Welcome to Hell

By the start of 1914, it would be safe to say that Alfred Adams was respectable entrepreneur and shopkeeper. It is worth remembering that he was still in his mid-20s. But the world in which he was making such quick headway was lost forever in summer 1914; a global war was sparked by the assassination of the Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo, in what is now Bosnia-Herzegovina. As the European powers declared war on each other, Alf might have felt a pang of regret he was not among the men rushing to fill the ranks in those heady summer days. But as a family man, he was not the sort of person the War Office wanted. It was the younger, unmarried men that were selected, and only those deemed fit enough.

The recruiters could still afford to be discerning in these early stages and there was a reason for this: most people predicted a short, sharp war followed by victory. Indeed, plenty of the raw recruits who passed the selection process openly worried the conflict might finish by the time they reached the front. Yet there were some, those with deeper foresight, who predicted a titanic struggle. This became apparent when the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France, a small but professional army, found itself in urgent need of those new recruits as the casualties started to climb. By 1915, those who had been turned away the previous summer were asked to volunteer again, with many joining-up through the Kitchener’s Pals Battalion scheme, whereby local units of friends or workmates were formed up and went to war together.

Alf might not have thought too much about the war's finer details as he and Joe would have struggled in 1914-1915 to overcome the loss of Beka and the fall in sales. Fortunately, as we have seen, the industry quickly bounced back after the first year of war and Coliseum tried to capture the patriotic mood by releasing military marches or instrumentals by military bands. There was even a patriotic design for 1914-1915 that incorporated a Union Jack and Royal Navy Jack. One of the songs sporting this particular label was ‘In Old Quebec’ backed with ‘United Empire’ and performed by the Winnipeg Light Infantry Band, something of a hit that cashed-in on the arrival of Canadian forces in Britain during 1915. They would be leaving for the Western Front shortly.

There is a small possibility that Alf enlisted in 1915 and then served as a regular, although this seems highly unlikely as there were simply too many risks and commitments at home. Alf was now a family man with two young boys to look after. But in 1916 universal conscription was introduced and all men of service age started to be called up. It became impossible to avoid the war, unless one was disabled or a conscientious objector who refused to work in non-combatant roles.* It is impossible to say when Alf received his call-up, although it is also unlikely he was involved in any of the campaigns in 1916. In all probability he was with the army by late 1916 or early 1917.

*They were seen by society as shirkers and cowards, a social stigma that very few wanted attached to their names.

Alf became a number on joining the army: no.98533. Basic training would have involved square bashing and, a little later, weapons handling. Much had been learnt over past two years of war and the new men at least had these advantages when trying to get to grips with their lives as servicemen. However, they also had a much greater idea of what to expect and how dangerous it would be. After training, Private Adams became a member of what the men half-jokingly called the PBI, the Poor Bloody Infantry. But given his technical knowledge and intelligence, Alf may have already been earmarked to join a relatively new formation called the Machine Gun Corps (MGC).

New Corps, new career

The MGC came into being in October 1915 and quickly earned an elite reputation. It was also well known for its fearsome casualty rates; because of their killing power, machine guns were prime targets for enemy return fire. Indeed, the MGC was nicknamed ‘The Suicide Club’ by their infantry counterparts because of this. Coming from the men who were expected to do the bulk of the fighting and dying, this wry but grim sobriquet was high praise indeed.

By the end of the war around 170,500 officers and men had served in the Corps. Of this figure, 62,049 were either killed or wounded. One of the strangest facets of the MGC was the way it was formed and the way it recruited. It started life by simply pooling together existing regimental machine gunners into the new corps. These soldiers and officers subtly broke uniform codes by continuing to wear their old cap badges. They would mix them up with their new MGC insignia, which was a pair of crossed Vickers .303-inch heavy machine guns. One veteran from 6 MG Coy* recalled this peculiar anomaly, pointing out that the mixed use of badges was later a sign of pride and veteran status: ‘I was sometimes asked why so many of 6 MGC Coy wore various regimental badges instead of our crossed guns … It was a hint to the rookies that they were veterans … I noticed this former regiment badge wearing in other units of the MGC right up to the end of the war.’

*Companies in the field ranged from No. 1-286. The MGC was reorganised in early 1918 and its companies were formed into battalions, taking their number from the Division with which they were attached. Thus Alfred’s company, No. 243, went on to become part of 31 MG Battalion, 31st Division.

Later on, most recruits were transferred from their initial regiment into the MGC directly after their basic training and this is probably what happened to Alf. The next stop for those selected was to attend a machine gun training course at a special MGC centre near Grantham, Lincolnshire. Grantham and its satellite depots and camps, such as Belton Park, were not particularly salubrious, although they were infinitely better than the front lines. In training, Alfred would have familiarised himself with the workings and intricacies of the Vickers machine gun, a relatively new weapon and one that was far superior to the older maxim guns preceding it.

According to a British Army 1917 press release held in the Imperial War Museum, the course at Grantham was meant to last ten weeks. In reality, it was often six weeks because of the demand for machine gunners at the front. Theoretically, five weeks were spent learning about the Vickers and how to handle gun stoppages. The men also learnt how to handle pistols, work with range finders and use clinometers, which measured the angles of a slope. Following this, the men spent three weeks studying ‘bench work’, where the gunners learnt about riveting and soldering. The men then studied joinery and carpentry skills in the final two weeks.

Alf became a team player and each gun was ideally manned by a crew of eight. Four men were involved in the firing, with the Number One being the man who did the shooting. The others were responsible for the sighting, preparation and the bringing up of ammunition. Crews in the field more normally numbered between four and six because of the manpower shortage. The men of the MGC were nicknamed Emma Gees* and they were proud of the role they had to play and the power their weapons had upon the battlefield.

*Say MGs quickly and out loud and you’ll see why.

By 1917, major advances in the art of handling machine guns had been made. They were frequently used in battery formations, laying down barrage fire onto the enemy at targets by map reference. Barrage fire was also useful in helping the infantry fend off enemy assaults or counter-attacks. Indeed, so effective was this method that advancing units were often shot to pieces in a hail of machine gun bullets before they even came into the range of defensive small arms fire. The British learned this the hard way during the initial offensives of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916.

Enfilade fire was used when the machine guns were carefully positioned to offer both support and covering fire. None of the guns were directly aimed ahead; instead, they were placed at angles of 45°, with one position facing leftwards and the other to the right, and so on down the appropriate frontage. This arrangement would create crossfire along a broad front, with the technique used either at close quarters or sometimes to deliver a barrage. Harassing fire was usually conducted by one or two guns aimed at specific enemy points, with short bursts fired at irregular intervals day and night. In skilled hands, and with its long range, the Vickers could also fire single shots at problematic targets, such as a sniper’s position.

Have machine gun, will travel

Despite the training Alf would have received, very little would have prepared him for the reality of life on frontline. Detailed knowledge of war could have only come from active service. Still, experience is only one side of the coin when discussing a soldier’s chances of survival. Luck is the other.

Alf’s team would have usually formed part of a four-gun battery. His gun mates would have been the members of his ‘trench household’ when in the line. It was to these people he would have day-to-day contact with, while Alf’s closest friends, or ‘mucking-in pals’, were those who he helped above all others and they would do the same for him. We can be sure that Private Adams was with 243 MG Coy when it was posted to the Arleux-Fresnoy and Oppy-Gavrelle sectors under the command of 31 Division. The company arrived on the Western Front on 18 July, 1917 and, as was standard practise, Alf drew up his army will on the following day.

‘In the event of my death I give the whole of my property and effects and monies in the bank to my wife, 132 Battersea Park Road, Battersea, SW.

PS any army money owing must be paid in full direct to my wife.’

The company had arrived in France a few days beforehand, on July 13, and had probably been processed at Camiers, a central MGC base near Etaples. Here they would have also tested the efficiency of their gas masks, a vital piece of equipment. Alf and 243 MG Coy then arrived in the Arras region of the Western Front, which had witnessed major successes just a few months earlier, most notably with the great Canadian victory at Vimy Ridge. As the Allies had pushed forward in this sector, the Germans retreated to vast, pre-prepared defence lines. In Alf’s zone, these stretched north to south from Acheville, around Fresnoy, on to Oppy and then past Gavrelle.

The fighting in this region had died down by July, with Flanders and other locations now the primary focus for British and Commonwealth attentions. But even on a ‘quiet’ sector, the chances of being killed or maimed could be high as there was a constant level of attrition from mortars, gas, snipers and artillery shells. Incidentally, large German 15 cm shells were known as ‘Jack-Johnsons’ in honour of the great American boxer and for the punch they packed. The village of Gavrelle had recently seen a localised offensive, which included a series of the bloody assaults by the Royal Naval Division that pushed the Germans just east of the village. However, one of the key features in the area was the site of a windmill (soon destroyed) that was located on higher ground to the northeast of Gavrelle. Great efforts had been made to take this location, but the Germans replied with concerted and successful counter attacks.

To the north, Oppy Wood had witnessed some particularly vicious fighting and, with its eerie and totem pole-like trees, became a well-known danger spot on the Western Front. It was later immortalised by John Nash in his painting Oppy Wood, 1917, Evening. As was often the case with the more lethal parts of the Front, British soldiers responded with a heavy dose of gallows humour; a gunner from number 205 MG Coy, who was at Oppy Wood in the spring of 1917, remembered being jokingly told that its name derived from the fact that the Germans and the British were continuingly ‘hopping in and out of the place’.

Fresnoy was just east of Arleux, a small but heavily-defended hamlet. A young German officer by the name of Ernst Junger was in stationed here during this period and would later record some of the horrors of this location in his famous work Storm of Steel. The Germans still held what remained of Fresnoy by the time Alf arrived, their lines looping around its shattered houses.* The landscape encountered was flat and fertile, and used for growing cereal crops. Because of the lack of cover, movement during daylight hours was a risky business, although many veterans and commentators noted the communication trenches in the area were in excellent condition. There were also numerous saps and galleries for the men to take cover in.

*Fresnoy had been taken by the Canadians after their thrust through Arleux. British and Canadian forces then lost Fresnoy over 7 May and 8 May, following ferocious German counterattacks.

Into the line

The journey from the comparative safety of the rear zones to the front was laborious and morale sapping. The men would be gathered together in marching order along with a transport section of mules responsible for delivering the machine guns as far as the support lines. A veteran from 62 MG Coy recalled the scene often resembled ‘[the] training days around the lanes of Grantham ... [but] as soon as the order “no smoking” was given, one sensed the nearness to this sector of the line we were to occupy’.

The men of 62 MG Coy arrived at the communication trenches at dusk and prepared themselves to take over from gunners now preparing to leave. ‘Each gun team took over its own guns and equipment and began the long trek through communication trenches to be allotted positions in the front line. Ammunition, water and rations all had to be manhandled, which entailed several journeys, before finally taking over from the outgoing gun teams.’ The work was backbreaking. ‘My shoulders and limbs felt pulverised,’ the veteran remembered. His section sergeant, an old soldier, grimly joked: ‘You’ll get used to it; if you live long enough.’

Given their role, the machine guns were always carefully sited and protected as well as could be, usually with sand bags. Sometimes the gun would be positioned in an ‘elephant shelter’, a sandbagged strongpoint with curved roof of corrugated steel. While it would not withstand a direct hit from larger calibre shells, an elephant shelter at least offered some elementary protection. The greatest danger was for the MG position to be registered by enemy observers, who, just like the British, kept a constant watch over the frontlines looking for threats and high-priority targets. Machine guns were both. If a gun emplacement was located, or even suspected of being present, then the Emma Gees could expect a dose of incoming fire to come their way.

During the lulls, Alf and his comrades would clean their machine gun and ready the ammunition, a job that always needed doing given the conditions. When in their dugouts, the men often spent time destroying an enemy disliked more than the Germans: lice. To confess to being ‘chatty’ was to admit to having lice, which almost all soldiers in the line suffered from. One way to try and kill these pests was to cross the seams of clothing over an open flame, the heat destroying the parasites and their eggs. Rats were also a problem, the men trying to invent fiendish ways to massacre these rodents. They met little success as this particular enemy appeared to have limitless reinforcements.

The food was fairly basic, frequently comprising bully beef, Tickler’s jam and other rations, all of which were stodgy and decidedly taste free. Cooking usually took place on a primus-like stove. Much of the food brought up the lines was transported in empty sand bags, the threads and fragments of which often cropped up as an unwanted dietary supplement. Water was commonly transported in disused petrol cans and drums, its taste nicknamed eau du essence.* For those who smoked there were army-supplied cigarettes, often a brand called ‘Three Witches’ that the troops derisively called ‘Three Bitches’ and, according to one account, reminded the smoker of seaweed. Parcels from home were keenly awaited, with socks and warm clothing the most popular items, particularly in the winter months. It appears that Alf was turning a shrewd profit by selling on the contents of parcels sent out to him and Lt Young alludes to this in his letter, with the inference that there was a fair sum of money involved.

*Franglais for petrol-flavoured water.

Catching out the enemy

The first positions 243 MG Coy occupied on arrival were in the support lines near Vimy and were probably located on the Farbus-Vimy-Levin line. These back areas, while safer, still remained in range of the heavier shells. Posted next to Willerval South, 243 MG Coy’s work became more intensive, with much of their time spent firing at strategic points held by the enemy at irregular intervals during the night. Often they were hoping to catch enemy working parties in the open. They would do this by whipping the bullets back and forth in a curving motion and along different angles. This action would have increased the chance of killing any enemy who had ducked at the first salvo and then stood up thinking the fire had moved along. That was often a fatal mistake.

There are numerous actions recorded in the Company diary along these lines, with cross roads and supply points 243’s favoured targets. For example, on 12 November, 243 MG Coy used enfilade fire on ‘ULSTER and FLICKER’ trenches ‘with the object of catching work parties at work on trench destroyed by artillery. Enemy retaliated on TIRED ALLEY. On information [from] our artillery that a relief was expected to take place in the enemy lines, short bursts of fire were concentrated on them in conjunction with the artillery at 8 pm, 10 pm, 11.15 pm, 1 am, 1.15 am, 1.25 am.’

Assuming that Alf was the Number One firing the gun, and bearing his musical knowledge mind, he might have hammered out a burst in time to a ditty. Strange as it may seem, but many gunners built up a ‘repertoire’ and, on a number of occasions, other guns would accompany the ‘song’, creating what the troops called a machine gun orchestra. Some of these gunners became well known in the sectors and were given nicknames like ‘Duck Board Dick’, ‘Parapet Joe’, or ‘Happy Harry’. But grandstanding in this manner could also help pinpoint the gunner’s position. One MGC veteran remembered how his unit, stationed on the Somme, smoked out a particularly annoying German counterpart this way. Although a fairly lengthy extract, it is worth highlighting.

‘We had a Number One who could play a tune on his Vickers; “pop-tiddy-pop-pop”. There was one German Maxim gunner among the group in the wood opposite who got into the way of reply with a slower “Poop-Poop”. That particular gunner was a nuisance to us, as his weapon was laid exactly to spray our dugout entrance to our rear. We lost more than one of our section going to and fro, especially when the rations were coming up at night. We decided to get rid of this “Poop-Poop” marksman.

‘We got two teams ready to move to left and right with periscopes,* at the blow the whistle. The next time that Fritz opened up, our Number One waited until there was a pause, and then played a “pop-tiddy-pop-pop”. Sure enough, the Jerry responded with a “Poop-Poop”, and exchanges continued while our watchman took exact sightings of his flashes, and drew converging lines on a trench plan until we had its position and range exactly. At dawn on the following day, Jerry began his usual pre-breakfast shoot-up. All our four guns had been carefully laid and, at the blow of the whistle, they all opened up on him and Jerry suddenly stopped in the middle of a belt. Over the next few nights we were able to carry out our ration fatigues uninterrupted.’

*To see safely over the trench parapets.

Barrages, bullets and gas

Above him, Alf would have heard the buzz of aircraft as the British and Germans vied for aerial supremacy in fierce dogfights. The area was noted for the number of crashed aeroplanes and one veteran recollected that there were a least ‘half a dozen pitiful wrecks dotting the fields near Gavrelle’. Fitting in with this, Alf’s company was involved in light anti-aircraft defence and there are a number of references in the diaries to fire being directed at the enemy overhead. For example, early in the morning of 26 August a number of 243’s guns forced off hostile aircraft flying directly above.

When the infantry initiated a raid, Alf’s company, possibly along with another machine gun unit – depending on the size of the action – might act in a support role and use the barrage technique. For example, ten guns were used to fire a barrage on September 13 two hours after the infantry had launched a successful raid on lines southeast of Arleux. The idea was simple but deadly: a wave of bullets would strike any enemy reinforcement parties sent into the area once the alarm was raised. Around 49,000 rounds were fired. Alf was also involved in a sizable operation on 9 November, with the diary recording that all 16 of the company’s guns were deployed alongside twelve guns of 94 MG Coy. This was a major effort and the details were scrupulously recorded, including the number of stoppages. The machine guns added to a creeping artillery barrage from 12 pm to 1 pm, with around 150,000 rounds fired.

Meanwhile, the horror of chemical warfare was never far away. At midnight, on 16 October, the Germans put down a brief barrage of high explosive and gas on the support lines, including 243 MG Coy’s positions. ‘The gas had an inflammatory effect and a foul smell. The double blankets at the entrances of the dugouts proved entirely satisfactory,’ the diary noted. ‘The gas had a very marked effect on the guns in the affected area, which could not be fired before they had been thoroughly cleaned,’ it adds. At the receiving end of this gas attack was the Accrington Pals Battalion, which suffered 35 casualties. However, the night’s disturbances were not over; at 6.00 am an SOS flare was fired over British front lines, bringing about a barrage of artillery support and, with their machine guns promptly cleaned and primed for action, fire from 243 MG Coy.

Alf was never constantly in the line: his company was relieved on a rotating basis. Marching back to billets in the rear zones, 243 MG Coy would return to the civilised world, which probably seemed a million miles away when at the front. Unlike many infantry units – who could be grabbed by the engineers to help work on repairing trenches and support lines – the Emma Gees were primarily concerned with equipment overhaul when out of the line. That said, it seems that 243 MG Coy was collared for the menial task of building winter standings for animals from August 6 to August 16.*

*Which was actually important work, although one can easily imagine what the average Emma Gee would have thought.

J Gadsby, of 142 MG Coy, also remembered these periods were often filled with ‘never-ending parades and field practice attacks, which, I am afraid, did not interest me much … The only thing one existed for was to lug boxes of ammunition here, there, and every old where, at the behest of one, two and three stripers and pippers.* What it was all about no one seemed to know or care. Just “muckin’ us abat” I think, to make us fit, and eager to do anything to ease the monotony.’

*Lance corporals, corporals, sergeants, lieutenants and captains.

Those who were ill faced a rather awkward situation. Because the MGC was hastily created, there was no cadre of Medical Officers (MO) within its ranks. Anyone feeling ill had to report sick and then trek to the medical officer of the nearest neighbouring unit. Emma Gees were quick to realise that there was silver lining within this. One veteran remembered how, as a wheeze, he and his comrades marched off to the nearest MO to report sick. The MO had them all take ‘number 9’ pills* and sent the lot packing. On the way back they made a surreptitious visit to a café and restaurant and undoubtedly this sort of incident was a common one.

*The number 9 was legendary for being dished out as a cure-all for every ailment. One veteran recalled that it ‘was expected to cure trench feet, the aching tooth and ingrowing toe nails, to lower temperature, restore lost appetite, regulate the pulse, heal the boil on the official place and cure scabies’. There was a widespread conspiracy theory that the number 9 was a placebo.

Evening entertainment of sorts was usually found at a local café or restaurant, although the troops were kept under relatively close scrutiny. The company was billeted in Roclincourt and Ecurie during Alf’s time and probably made use of whatever establishments were to be found there. The wine was no doubt awful and it is said that the British term ‘plonk’ for cheap or foul wine comes from the Great War when British soldiers mispronounced the French word blanc. For Alf there was the sad and unknown fact that Roclincourt would eventually be his final resting place.

Final days

Alf Adams was killed on 26 November 1917. Just before his death some major events had taken place: the Bolsheviks initiated their revolution in Russia early in November, while Georges Clemenceau became premier of France on 15 November. But more important, as far as Alf was concerned, was the Battle of Cambrai occurring just southeast of the Arras region. Tanks had been used in concert and in appreciable numbers for the first time on 17 November and had made a notable impact against the Germans. However, the ground that had been gained was soon being eaten away by strong counter attacks.

On 24 November, 31 Divisional Command was concerned that the Germans were moving units away from Oppy-Gavrelle sector to support their efforts at Cambrai. The division decided to direct artillery fire on German lines in an effort to provoke counter fire ‘and make him give away his arty dispositions, it not being known whether he has taken away any artillery from the area to the CAMBRAI front’. Meanwhile, 243 Coy had arrived in the immediate support lines of Oppy-Gavrelle sector, possibly between Tyne Alley and North Tyne Alley, which was unfamiliar territory. Although they were now much closer to enemy positions, the job remained the same. For example, on 20 November the diary records ‘1,000 rounds were fired at irregular intervals throughout the night at targets Gavrelle, Fresnes les Moutauban Road.’ This road was also targeted the following day.

The next few days were all noted as quiet in the company diary, with relatively little enemy activity to report. For Alf and his gun mates 26 November probably began like any other, with the team kept busy with all the usual concerns that filled the lives of Emma Gees. But today their number was up. German observers had carefully registered their position and a small barrage had been called for … And another four men lost their lives on the Western Front:

99641 Private J Walker

98531 Private W S Rowe

98911 Private G Jennings

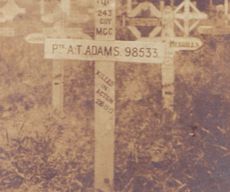

98533 Private A Adams…

Broken shards (CLICK TO CONTINUE)

Below: Click on the YouTube clip to listen to 'United Empire' by the Winnipeg Light Infantry. Click on the gallery below to view images of Alf at Grantham; a Vickers .303 being used for anti-aircraft purposes; a burial party that may have been like the one Alf received; Alf's original grave marker; the field and rough spot where Alf fell today; a memorial to the MGC in France.